Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

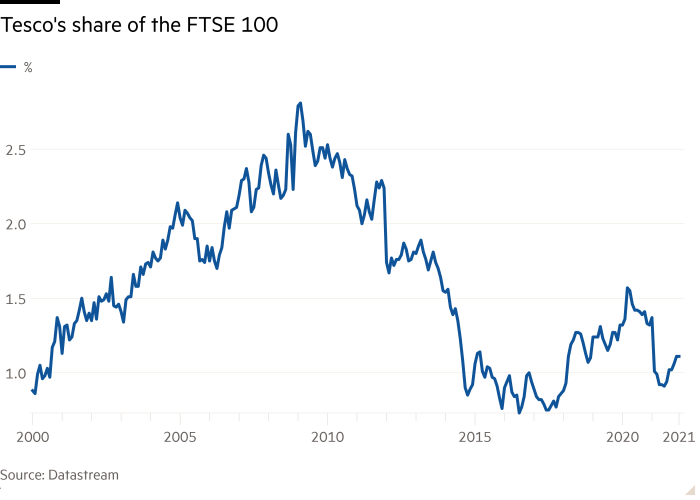

Much about the 2020s has a nineties feel. Think wide-leg jeans, the Robbie Williams biopic — and the resurgence of UK retail juggernaut Tesco.

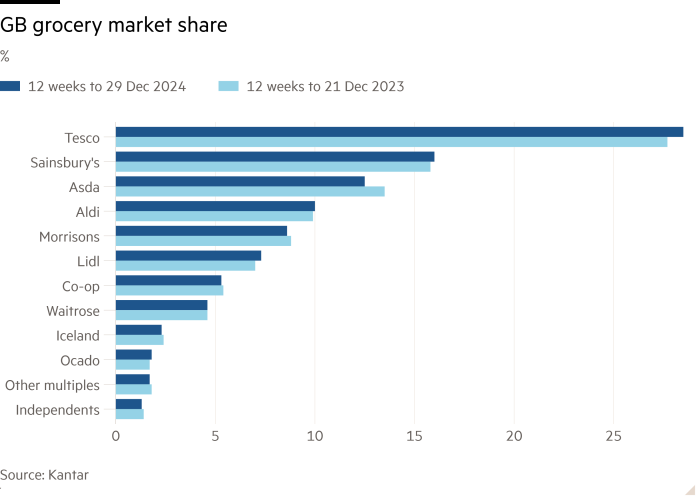

Britain’s answer to Walmart beat market expectations over the Christmas and third-quarter trading period, with like-for-like retail sales improving 3.1 per cent. But it’s also rising in relative terms. Tesco’s market share has increased for 19 consecutive periods and is now at 28.5 per cent, its highest level since January 2016, according to Kantar.

Granted, retail has had a choppy start to the year, as investors fret about higher costs arising from the Budget and economic surveys projecting gloom. Tesco’s shares traded lower on Thursday morning, possibly because it didn’t upgrade its full-year profit guidance. It still expects adjusted operating profit this year from its retail business of around £2.9bn, about 5 per cent higher than a year earlier.

Nevertheless, Tesco’s shares have outperformed over the past 12 months. It trades at 13.5 times forward earnings compared with rivals such as Marks and Spencer and J Sainsbury, which are on about 12 times, according to FactSet numbers. Several advantages make it deserving of that premium.

First, several of Tesco’s competitors are weakened by troublesome debt burdens. Asda’s share of the market, for instance, has dropped to 12.5 per cent compared with 13.5 per cent a year earlier.

Tesco’s retail operations, meanwhile, generate plenty of cash, allowing it to invest in grabbing further share. Share buybacks have also kept investors happy. There should be about £1bn of those this year.

But Tesco’s recent success is also partly due to self-help. Since the turn of the decade, it has been slowly but surely fighting back against the assault of the German discounters, Aldi and Lidl. Its “Aldi price match” scheme has altered the perception in shoppers’ minds that the discounters were where they had to go to get basics at a good price, says PwC’s senior retail adviser Kien Tan.

Back in the 1990s, one of Tesco’s smartest moves was the introduction of the Tesco Clubcard loyalty scheme. Today, it has more than 23mn UK households signed up. But despite the programme being 30 years old, chief executive Ken Murphy has hinted that Tesco is still only at the foothills of using its valuable data, plus artificial intelligence, to tailor offers to customers.

Britain’s grocery sector remains a highly competitive, low-margin business with little room for error. Tesco can still receive drubbings on social media for the state of its stores and offers. While the 1990s saw Tesco in the ascendant, the 2000s brought a backlash on everything from its urban planning impact to supplier relations. A moment of nostalgia is no reason for Murphy to stop looking ahead.