When many stars reach billions of years in age and run out of fuel, they become dying stars known as red giants. The stars expand and can engulf nearby planets, effectively incinerating them.

In approximately five billion years, Earth’s own sun will turn into a red giant and engulf planets, including our blue marble.

While astronomers have identified many of these red giant stars, it was only recently that the process of eating a planet had been directly observed.

Astronomers have identified many red giant stars and suspected that in some cases they consume nearby planets, but the phenomenon had never been directly observed before. In 2023, scientists discovered a star nearing the end of its life had swelled and absorbed a planet that is likely about the size of Jupiter.

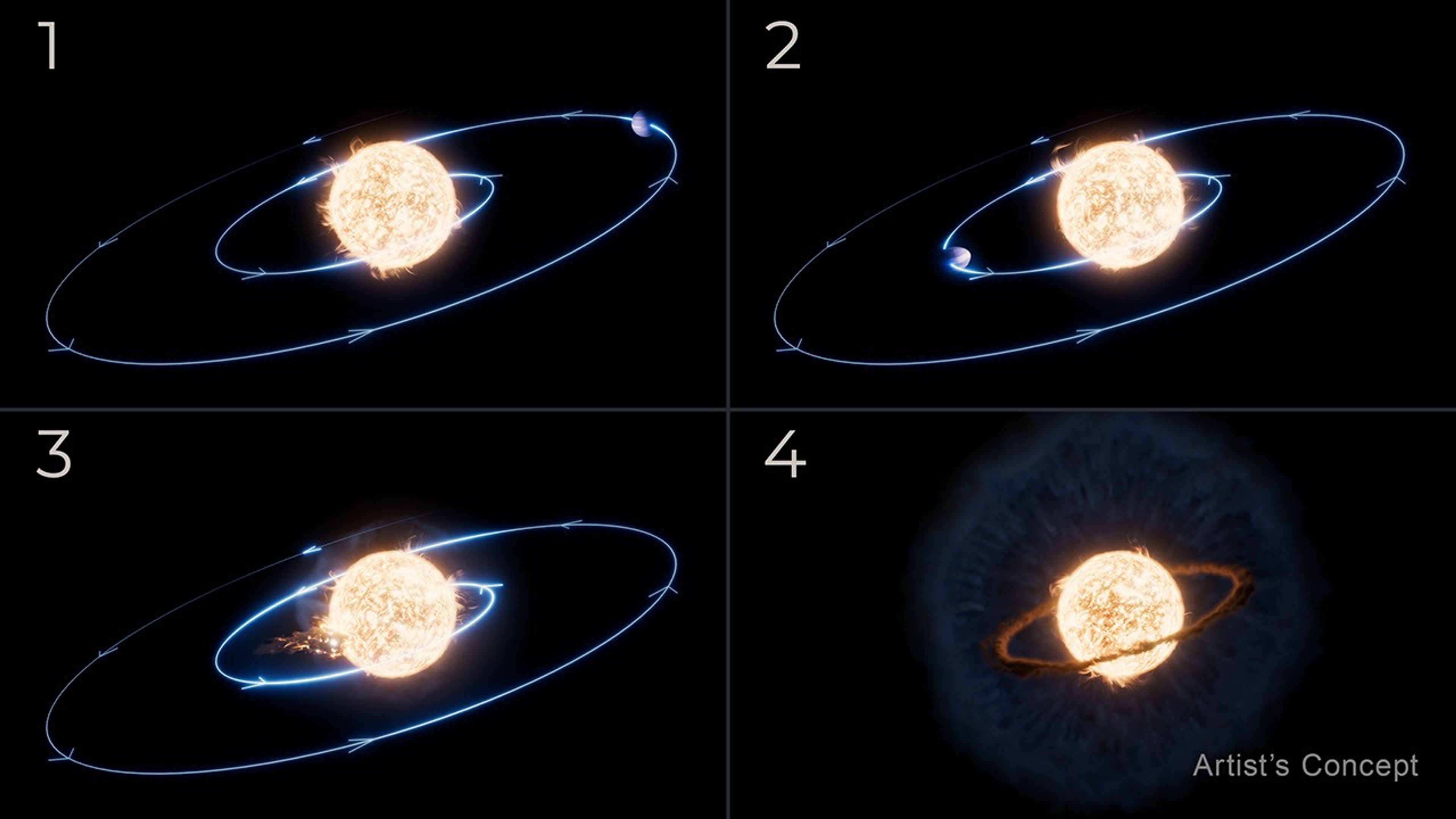

Now, with additional observations from the James Webb Space Telescope, they say there’s been a “surprising twist.” Instead of eating the planet, Webb’s observations show the planet’s orbit shrank over millions of years, pulling the celestial body closer to its demise until it was fully engulfed.

“Because this is such a novel event, we didn’t quite know what to expect when we decided to point this telescope in its direction,” Ryan Lau, an astronomer at the National Science Foundation National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory in Tucson, Arizona, said in a statement. “With its high-resolution look in the infrared, we are learning valuable insights about the final fates of planetary systems, possibly including our own.”

Lau is the lead author of a new paper published Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal.

Using the telescope’s Mid-Infrared Instrument and Near-Infrared Spectrograph, the researchers examined the Milky Way galaxy scene about 12,000 light-years away from Earth.

While the sun had been recognized as more like our sun, a measurement from the Mid-Infrared Instrument found the star was not as bright as it should have been if it had evolved into a red giant. The finding indicated to researchers that there was no swelling to engulf the planet, as once believed.

“The planet eventually started to graze the star’s atmosphere. Then it was a runaway process of falling in faster from that moment,” team member Morgan MacLeod of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explained. “The planet, as it’s falling in, started to sort of smear around the star.”

The planet would have blasted gas away from the outer layers of the star.

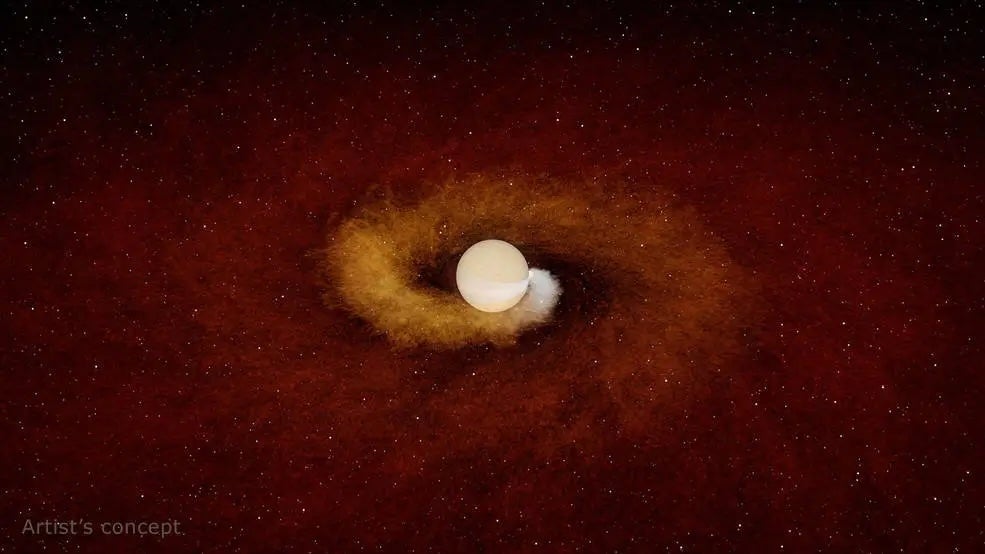

The Near-Infrared Spectrograph revealed a hot disk of molecular gas surrounding the star, where carbon monoxide was detected.

“With such a transformative telescope like Webb, it was hard for me to have any expectations of what we’d find in the immediate surroundings of the star,” said Vassar College’s Colette Salyk, an exoplanet researcher and a co-author of the new paper. “I will say, I could not have expected seeing what has the characteristics of a planet-forming region, even though planets are not forming here, in the aftermath of an engulfment.”