Red tape may feel like a modern-day frustration, but according to archaeologists, it’s been a part of governance for millennia.

Evidence from ancient Mesopotamia reveals that bureaucratic systems were in place as far back as 4,000 years ago.

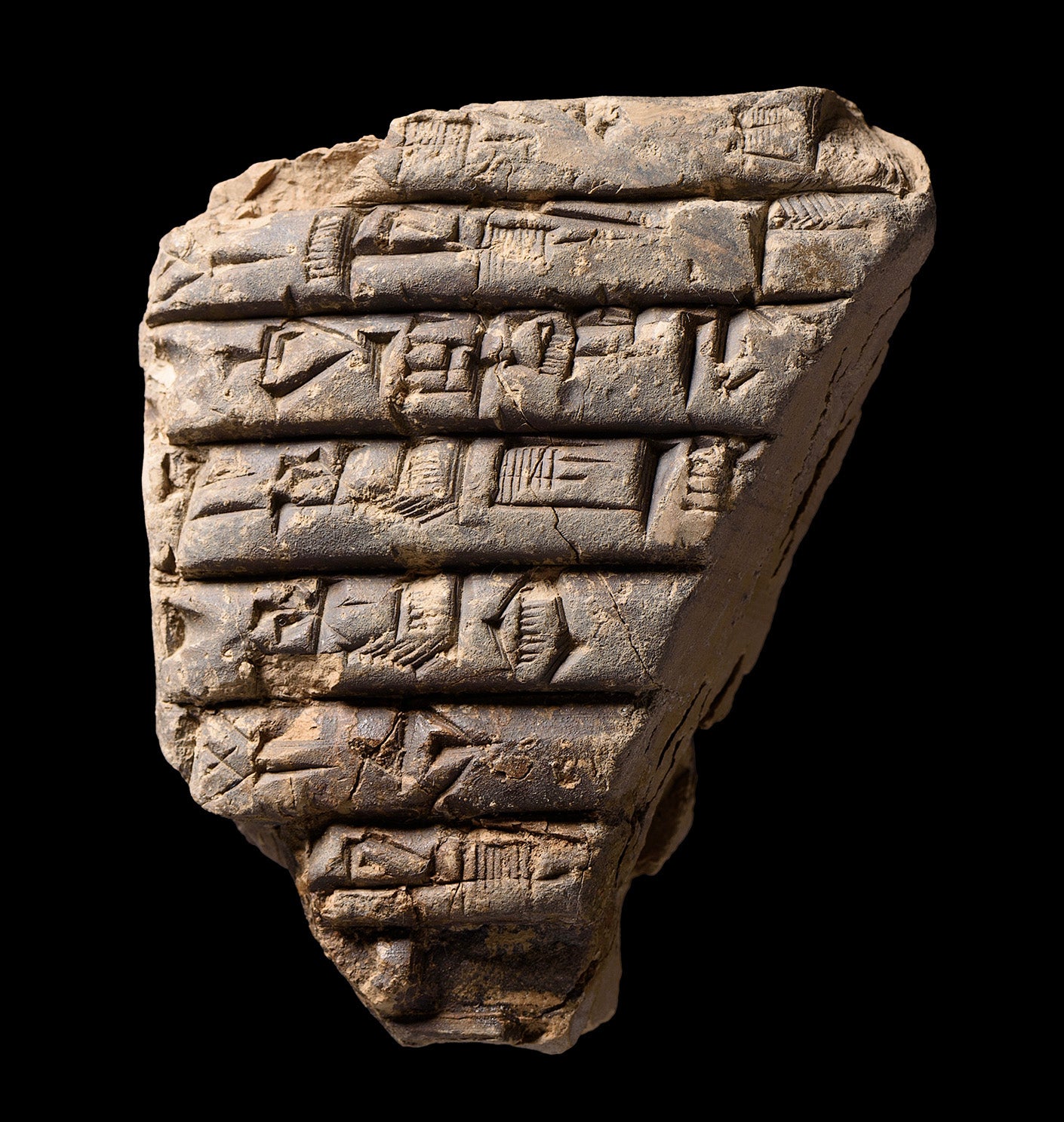

Over 200 administrative tablets and around 50 cylinder seal impressions of Akkadian administrators have been uncovered by archaeologists from the British Museum and Iraq’s State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, shedding light on the early foundations of government bureaucracy.

The texts reveal a complex bureaucracy that went into running the ancient civilisation.

These were the state archives of the ancient Sumerian site of Girsu, in modern-day Tello, while the city was controlled by the Akkad dynasty from 2300 to 2150BC.

While the texts may not be great masterpieces of Sumerian literature, like the Epic of Gilgamesh, the British Museum’s curator for ancient Mesopotamia, director of the Girsu Project, Sébastien Rey told The Independent they are “nonetheless incredibly important.”

“They record all aspects of Sumerian life, and above all they name real people, their names, their jobs,” he said.

“The new tablets and sealings provide tangible evidence of a Sumerian city and its citizens under Akkad rule which will last about a century and half before the fall of the empire.”

Girsu, known as one of the world’s oldest cities, was once revered as the sanctuary of the Sumerian heroic god Ningirsu.

At its peak, it covered hundreds of hectares worth of land, but it was one of the independent Sumerian cities that were conquered around 2300BC by the Mesopotamian king Sargon.

Sargon originally came from the city of Akkad, whose location remains unknown but is thought the be near modern Baghdad. The Akkadian empire lasted for 150 years, ending with a rebellion.

These administrative tablets, containing cuneiform symbols, an ancient writing system, record the affairs of the state, including issues relating to land management and the movement of goods and service.

There are accounts of various commodities, including deliveries and expenditures, birds, fish and domesticated animals, flour and barley. They also deal with goods such as bread and beer, ghee and cheese, wool and textiles.

He said: “The names and professions of the citizens of Girsu are recorded in lists. Sumerian cities were known for their complex bureaucracy.”

“Among the many examples for concrete imperial control is the use of the newly imposed standard system of measures, the so-called ‘Akkad-gur’ for flour and barley,” he continued, comparing it to the British Imperial Unit.”

The tablets were found at the site of a large state archive building, which was made of mud-brick walls divided into rooms or offices.

Mr Rey added: “We also found a group of tablets containing architectural plans of buildings, field plans and maps of canals. These were drawn by surveying scribes of the administration and are among the earliest known in the world.”

The finds will go to the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad. It’s possible they could be loaned to the British Museum in the future once further research and study has been carried out on them.